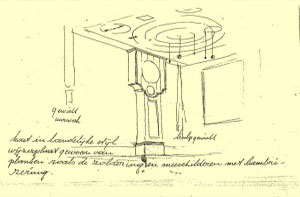

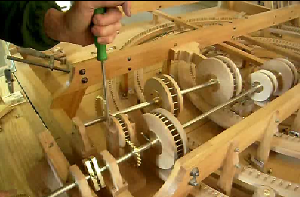

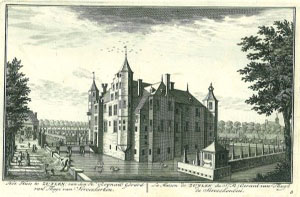

Planetarium Zuylenburgh in Oud-Zuilen was completed in 2009. It is the second planetarium in Holland. The planetarium of Eise Eisinga in Franeker was set as example, although some new insights have let to a unique example of Planetarium Zuylenburgh tot een uniek voorbeeld van contemporary artisan work. The creation of Planetarium Zuylenburgh took three years to complete and is entirely built by hand.